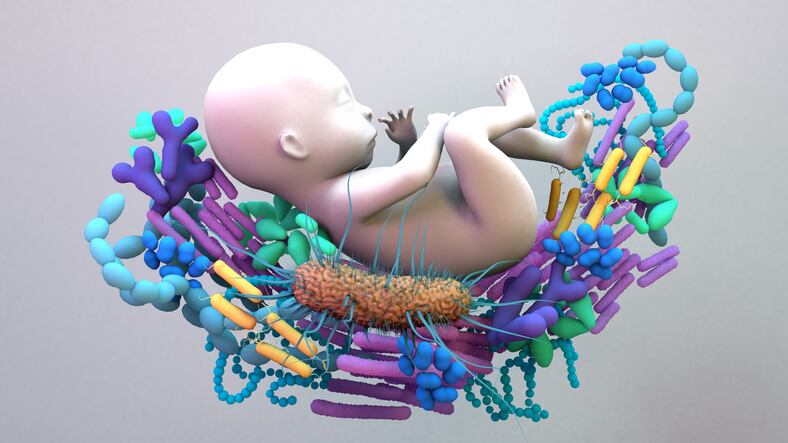

While most human microbiome research has focused on bacterial communities, the advancement of high-throughput sequencing has led to the ability to study gastrointestinal tract mycobiota.

However, a new report published in Advances in Nutrition noted that the studies that have been conducted on the mycobiome have involved adults.

The team of U.S. researchers compiled the latest research in this space, concluding that the small body of research into children so far suggests that alterations in mycobiota are associated with health conditions like allergies, type 1 diabetes and autism symptoms.

“Despite the lack of literature describing the mycobiome, we would be remiss not to discuss the importance of how fungi interact with other microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract,” they wrote. “With our current limited understanding of the role of fungal species in developing early microbiomes and the immune system, we must direct research toward maternal and infant hosts in various environmental conditions and across diverse geographic locations.”

Responding to this report, Dr. Mahmoud Ghannoum, co-founder of microbiome R&D company Biohm, the first to discover and name the community of fungi in the gut, noted that recent publications have established that not only do bacteria and fungi coexist in different body sites, they also interact and cooperate in a way that affects host health.

"Therefore, it is critical to take both bacteria and fungi into consideration when you are developing a product to positively modulate the microbiome," he said.

Explaining why there is a lack of expertise in the study of fungi, Dr. Ghannoum added: "One of the first steps to analyze the microbiome is extracting DNA from both bacteria and fungi. The first step to get the DNA from these microbes is to breakdown the cell wall (the outer cell envelope).

"Breaking the cell wall of bacteria is much easier than breaking the fungal cell wall where you need to use very high pressure and/or enzymes that can degrade the fungal cell wall. Failure to do so will impede our ability to get enough fungal DNA to analyze the mycobiome."

The complex interplay

Previous research indicates the interaction between bacteria and fungi is specifically required for nutrient metabolism, modulation of the host immune system and metabolite production.

The authors noted that an improved understanding of these complex interactions is essential in developing products to shape human health.

“With the increase in popularity of use of probiotics, it would be important to understand the role of probiotic supplementation on mycobiota composition and function and determine how those changes impact the host,” they wrote.

So far, only one study has investigated how supplementation of the maternal diet with a probiotic affects the gut mycobiome. The research concluded no effect on infant gastrointestinal tract mycobiota composition when pregnant women were supplemented with probiotic milk containing lactobacillus and a bifidobacterium. However, mothers who received supplementation harbored a higher abundance of total fungal DNA and a lower abundance of S. cerevisiae.

A 2020 study in mice found co-colonization with other microbiota alters the relative abundance of fungal species and significantly increases alpha diversity.

One species of fungus, C. albicans, is negatively associated with several bacterial species (L. reuteri, Muribaculum intestinale, Flavonifractor plautii, Turicimonas muris, Bifidobacterium longum and Clostridium clostridioforme) and positively correlated to other fungi (I. orientalis, Candida parapsilosis, R. mucilaginosa) and bacterial species (C. clostridioforme, Blautia coccoides, Enterococcus faecalis and M. intestinale).

Infant mycobiota—the science so far

Postnatal diet influences the mycobiome, with known differences between formula- and breast-fed infants, as well as changes in children receiving vitamin supplementation. For example, M. globosa features prominently in the gut mycobiome during the first three months of life of human milk-fed infants.

Previous research found vitamin A supplementation was associated with a higher fungal alpha diversity in toddlers.

A 2021 study involving 80 children 12 and 24 months of age concluded that vitamins and iron may promote colonization with the detrimental parasite protozoa and the group of fungi named mucormycetes (linked with the rare fungal infection mucormycosis), whereas the addition of zinc appeared to ameliorate this effect.

Mucormycetes is a fungal taxon known to cause mucormycosis, a symptomatic respiratory and skin infection that can be fatal if left untreated.

Mycobiota and health outcomes

In adults, mycobiota composition change has been reported in IBD, diabetes, schizophrenia, C. difficile and Crohn’s disease, but the majority of studies with children focus on allergies.

The limited research has found Alternaria, Cladosporium, Saccharomyces, Acremonium and Rhizopus increase with atopies. This is likely due to these species supporting the production of metabolites that could provoke an altered inflammatory state.

In fact, in a case–control study of atopic wheeze subjects, P. kudriavzevii and Saccharomyces were more strongly associated with asthma risk than microbiota composition.

Research looking into the association between the gut mycobiome and atopic dermatitis in 9- to 12-month-old infants found most of the fungal proteins of Acremonium, Wickerhamomyces, Rhodotorula and Rhizopus were significantly increased in the persistent atopic dermatitis group, suggesting they were not only present but also metabolically active in infants’ guts.

The most common fungal species associated with multiple health outcomes, is Candida. An abundance of Candida has been shown to increase in atopies, focal intestinal perforation, autism disorder and IBD, whereas in type 1 diabetes and obesity, its abundance was lowered, suggesting fungal abundance change could be disease-specific.

Dr. Ghannoum's nutrition tips

There are three basic principles:

- High-carb diets (especially sugar) increase fungi including Candida (this is detrimental).

- Vegetarian diets, with their typically higher content of vegetables, fruit and whole foods generally induce more favorable microbiome compositions

- A higher proportion of amino acids (protein) and fatty acids (certain healthy fats) are key to inhibiting fungal overgrowth.

Focus primarily on whole foods - No processed foods or packaged foods with more than three ingredients.

Take smaller portions of prebiotic fibers spread over the day.

Candida favors an inflammatory state so try anti-inflammatory foods such as ginger, turmeric, DGL (deglycyrrhizinated licorice) and marshmallow root.

Discourage Candida with these additional supplements:

- Multivitamin - Vitamins A, C and B (especially B6), as well as those related to gut healing - zinc, vitamin A, and vitamin C.

- Probiotic - Ideally one that contains S. boulardii. This beneficial fungal strain works to balance Candida levels and reduce biofilm development to support overall microbiome health

- Antifungal supplements - Especially those containing garlic, polyphenols and grape-seed extract.

Source: Advances in Nutrition

doi: 10.1016/j.advnut.2024.100185

“The Role of Early Life Gut Mycobiome on Child Health”

Authors: K.A. Rodriguez et al.