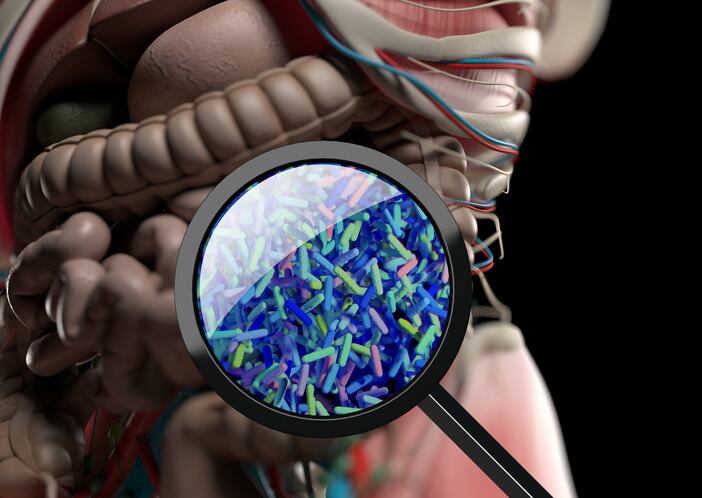

The word 'synbiotic' appears on a growing number of food and supplement products, with synbiotic ingredients showing promise for modulating the community of microbes living in the human gut, while providing a health benefit.

Synbiotics are generally understood to be a combination of a probiotic and a prebiotic but experts have deemed this description too limiting for innovation in this field and too ambiguous to allow for a clear understanding of synbiotic health benefits.

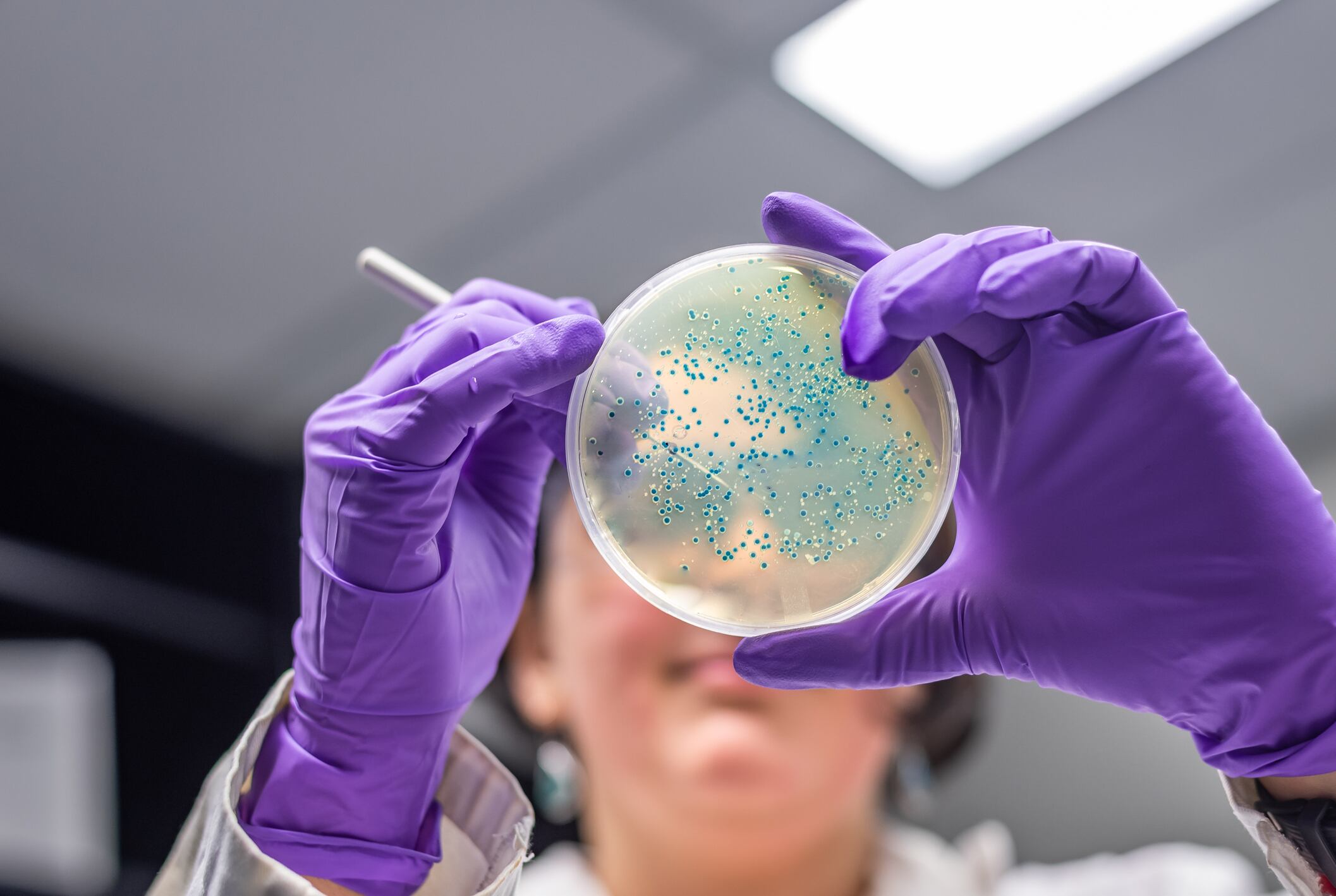

To address the scientific ambiguity around synbiotics, a group of 11 leading international scientists formed a panel to create a consensus definition and to clarify the evidence required to show synbiotics are safe and effective.

In a paper published in 'Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology', the authors advance a new definition of synbiotics, which is informed by the latest scientific developments in the field: "a mixture comprising live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilised by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host."

The experts on the panel emphasise that the definition is designed to be inclusive - many different combinations of live microorganisms and selectively utilised substrates could qualify as synbiotics, as long as a human study demonstrates the health benefits of any particular combination. Also, synbiotics need not be limited to the gut; they could potentially target any part of the human body that harbours a community of microorganisms.

"We hope the publication of this definition will mark a shift in people's understanding of synbiotics," says first author Kelly Swanson, Professor in the Department of Animal Sciences and Division of Nutritional Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "We can begin discussing synbiotics in a more scientifically accurate way, giving everyone a shared vocabulary for understanding what they do, how they work, and what evidence is needed to meet the definition."

In the publication, the group also makes a distinction between 'complementary synbiotics', in which a probiotic and prebiotic are combined but work separately, and 'synergistic synbiotics', in which the selectively utilised substrate specifically feeds the microorganisms that accompany it.

The expert panel was convened by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), the non-profit organisation that previously led the scientific consensus definitions of both probiotics and prebiotics.

"Creating a definition of synbiotic is a first step," says Mary Ellen Sanders, ISAPP's Executive Science Officer. "From here, the scientific community can focus on designing and carrying out studies to test the health effects of these products."

Evidence required

The report outlines the level of evidence required for a product to be referred to as 'synbiotic'.

It states: "A synbiotic must contain a live microorganism and a selectively utilized substrate. For complementary synbiotics, the respective components must fulfil the evidence and dose requirements for both a probiotic and prebiotic. Furthermore, the combination must be shown in an appropriately designed trial to confer a health benefit in the target host.

"A product containing a probiotic and a prebiotic that only has evidence for each component individually, and not as a combination product, should not be called a synbiotic. A key evidentiary requirement for a synergistic synbiotic is that there be at least one appropriately designed study of the synbiotic in the target host that demonstrates both selective utilization of the substrate and a health benefit."

It adds that evidence required must be appropriately designed, with adequately powered experimental trials conducted on the target host.

"These studies should follow standard human trial design and reporting guidelines and consider best practices for diet–microbiota research. The study should also meet the criteria outlined in CONSORT and should be registered, including a description of all outcomes, prior to recruitment."

CONSORT criteria include guiding principles for microorganisms, microbiota-related compliance and outcome measures, relevant subgroups, and statistical considerations for evaluating the microbiota as a mediator of clinical effects.

The report adds that ideally, the health benefit of a synbiotic would be superadditive - better than the sum of the individual components. However, owing to the difficulties in demonstrating different levels of health benefit in an efficacy trial, the panel did not insist upon this aspect. Instead, they advocate requiring a measurable, confirmed health benefit of the synbiotic, which is conferred, at least in part, through selective utilisation of the substrate(s) provided in the synbiotic.

"Although in vitro and animal models are used frequently to test the effects of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics, it is our position that these have not been fully validated as predictive and that definitive tests of these interventions must be performed in the target host."

The panel also state that the health benefit of the synbiotic mixture be confirmed, even when established probiotic(s) and prebiotic(s) are used to formulate components of the synbiotic, in order to account for any potential antagonistic effect of the combination that might diminish the health benefits of each component independently.

"In the absence of evidence that the combination product provides a health benefit, a product should simply be labelled as 'contains probiotics and prebiotics'," the report states. "Sanders et al. provide a perspective on determining whether evidence from studies using one formulation (for example, a prebiotic or a probiotic alone) can be extrapolated to different formulations (for example, when combining a prebiotic and a probiotic)."

Source: Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Sanders. M. E., et al

"The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics"