Is FDA doing enough to stem tide of tainted products? Probably not

A look at databases compiled by the American Herbal Products Association in the weight loss and sexual enhancement realms (two categories of high concern for FDA) reveals a couple of important points: the existence of repeat offenders on these lists and the high number of ‘public notifications’ among the enforcement actions taken by FDA. Delving a little deeper shows the length of time between when a company putting out tainted products first comes onto FDA’s radar and when an enforcement action of some sort is undertaken. Sanctions can range from the aforementioned notifications up to recalls or, far more rarely, injunctions or criminal prosecutions. This period before an enforcement action is undertaken can stretch from months to more than a year or even into multiple years.

Calls for enforcement

The fact that tainted products can linger on the shelf is of concern to the dietary supplement industry. Frequent calls have been made by industry stakeholders for FDA to step up enforcement, in terms of both speed and comprehensiveness, both to better protect public health and to ward off criticisms of the state of the industry under DSHEA. It’s not fair to criticize the umbrella law under which the industry operates if it’s not being adequately enforced, stakeholders say.

Gary Coody, a health fraud coordinator in FDA’s division of enforcement, spoke with NutraIngredients-USA about how FDA goes about its enforcement duties. The agency uses the tools it has to the best of its ability, he said.

“FDA has available civil or criminal type of actions that we can take. In the criminal realm, the time frames are determined by the Department of Justice. That is somewhat out of our control. And whether to bring an action is always determined on a case-by-case basis. The egregiousness of the act and whether someone has been harmed would make us more intent on stopping the illegal act,” Coody said.

Small production runs

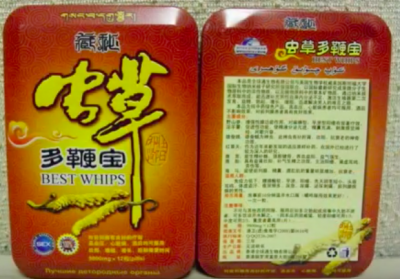

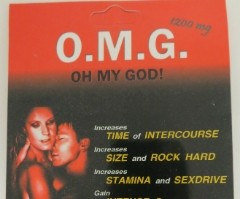

Many products listed on AHPA’s databases appeared to be small lot products and in some cases were sold in single serving blister packs. Many of these products appeared to be the sort that could be put on the market quickly and vanish just as quickly, only to show up under another guise. Coody said using a public notification in this cases was appropriate, both because finding these manufacturers is tricky and time consuming, and the small lot sizes presented a lower overall risk to public health. Public notifications merely warn the public of the tainted product, listing the adulterants in the product and give consumers contact information at FDA for more information.

“We have limited resources to go around for the number of unscrupulous sellers out there. The whole system is set up to respond to risk. We take enforcement actions that would have the greatest overall outcome the greatest deterrent effect,” he said.

“A public notification is a means to quickly notify the public about a tainted product,” Coody said. It is the first step in the enforcement process that could in some cases progress to recalls or injunctions, he said.

That is not to say that the risk presented by the small lot products is zero, Coody said. The risk to the public at large might be low, but the risk to an individual consumer might be grave. The most common undeclared pharmaceutical ingredients found in these products are sildenafil (Viagra) or taldafil (Cialis) or analogues in the sexual enhancement products and sibutramine or phenolphthalein in the weight loss products. The legal ED drugs contain warnings on their labels about side effects and contraindications, and sibutramine has not been legally on the market at all since 2010, when it was removed over concern about cardiovascular health risks. Not only are these ingredients not declared (so unwitting consumers wouldn’t even know they are ingesting them), but dosages remain a mystery, and in some cases are extreme, Coody said.

“In the case of sibutramine in weight loss products, in some cases we have found dosages of 10 to 30 times the former approved dose. It’s a troubling trend,” Coody said.

The review of the lists complied by AHPA seems to indicate that enforcement is indeed on the rise. But Coody said even with FDA’s greater efforts, there is little reason to believe the problem is getting better.

“I think it is an enormous problem. We can only test a small percentage of products. We have no way to estimate how many tainted products are out there. We don’t think they have decreased,” he said.

Aversion to risk

Jason Sapsin, an attorney in the firm Fox Rothschild, has some insight into FDA’s plight from his stint as counsel at the agency. Sapsin said the agency’s response the tidal wave of tainted products is complicated both by resource limitations and an institutional aversion to risk.

“There are so many resource limitations and then there is the question of the agency’s will to enforce. The resource limitations come in the form of a limited number of inspectors to go out and do inspections and take samples. Then are there are there enough compliance officers to evaluate the cases, enough lab capacity to run the tests and so forth.

“Then there is the issue that the agency is extremely reluctant to lose cases, so it works extremely hard to gather all the facts it can to be very procedurally very exacting both in the policy it imposes on itself and in fulfilling the legal requirements for filing a complaint. It all results in significant under-enforcement,” Sapsin said.

Is it enough?

Sapsin said in years past there was a culture at FDA that downplayed enforcement and emphasized FDA’s role as industry partner and teacher. That has changed in recent years, with enforcement now on the front burner. But it takes time for that sort of cultural shift to filter though a big organization, and Sapsin said he doubts that the political will exists to really change the fundamental resource limitations that FDA operates under.

“We are fortunate here in the US. By the global standards of public health disaster, with high morbidity, the US has not had one of these events. We do have bad events, but there has not that level of death that would make either the political system or industry or apparently the public sit up and say, things have got to change,” Sapsin said.

“The relative ease with which companies can move into and out of this marketplace means there is a huge upside for companies that want to game this system. There are more more targets for enforcement and the agency is more willing to pursue these companies and enforce the law. But the real question is, is it enough? The answer is, probably not.

“The question of whether to give a regulatory agency like FDA more resources is unfortunately a highly political question and from a public health standpoint it ought not to be,” he said.

“We are often asked if we need more resources. It’s not really our place to ask; we utilize the resources that were mandated and appropriated through Congress,” said Chris Kelly, a press officer at FDA.