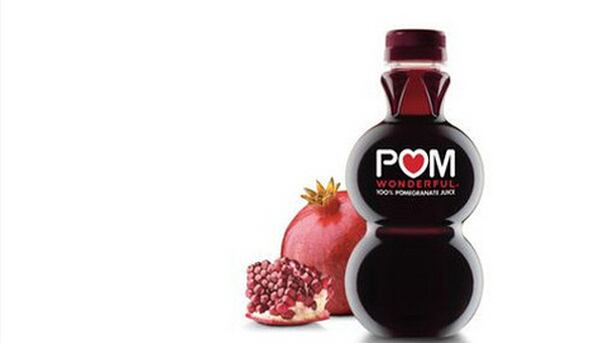

For a quick re-cap: The Supreme Court is looking at a false advertising suit filed by POM under the Lanham Act accusing Coke of “willfully misleading consumers” by marketing a juice comprised almost entirely of apple & grape juice as ‘Pomegranate Blueberry' (Coke says it complies with federal juice labeling laws, which trump Lanham Act claims).

Justice Kennedy: ‘I think it's relevant for us to ask whether people are cheated’

As the transcript of Monday morning’s oral arguments reveals, Coca-Cola faced several tough questions, particularly from Justice Kennedy, who asked whether Coke believed “that national uniformity consists in labels that cheat the consumers like this one did?”

Regardless of whether the label on the product in question complied with the letter of the law governing juice labeling, he added: “I think it's relevant for us to ask whether people are cheated.”

He went on to observe: “You want us to write an opinion that says that Congress enacted a statutory scheme because it intended that no matter how misleading or how deceptive a label it is, if it passes the FDA… there can be no liability. That's what you want us to say?”

Later, prompting laughter from the gallery, he said: “Don't make me feel bad because I thought that this was pomegranate juice.”

It looked like Justice Roberts was leaning in POM’s favor

While Coca-Cola’s attorney- Kathleen M. Sullivan, a partner at law firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan - did an extremely good job at articulating Coke’s position, Justice Kennedy’s sympathies seemed to lie with POM, noted Rob Bader, attorney in the San Francisco offices of law firm Goodwin Procter.

“The skepticism level was quite high for the Justices that questioned Coke, especially Kennedy, who used the word ‘cheating’ to describe Coke’s label. It also looked like Justice Roberts was leaning in POM’s favor. It looks like they are going to have some difficulty in constructing an argument in Coke’s favor.”

While some observers regard this as a classic case of the “pot calling the kettle black” given that POM has itself been accused of making wildly exaggerated claims about its products (covering everything from heart disease and prostate cancer to erectile dysfunction), it seemed “clear that the Justices who spoke favored POM’s arguments”, said Bader.

The Justices seemed to have a hard time grappling with the notion that there was no legal recourse for POM

The Justices seemed to be particularly uncomfortable with the notion that a label - however misleading - could be immune from a Lanham act claim because it is compliant with the relevant food labeling legislation, added Claudia Vetesi, an associate in the San Francisco office of Morrison & Foerster LLP.

“The Justices seemed to have a hard time grappling with the notion that there was no legal recourse for POM.”

Justice Sotomayor: You're permitted to use this name. But are you permitted to use it in a misleading way?

Justice Ginsburg, for example, wondered whether the Lanham Act (a federal false advertising law typically invoked in disputes between rivals) and the Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act (FDCA), which covers food labeling, “are serving different purposes”.

He added: “The law that you [Coca-Cola] are relying on is supposed to be concerned with nutritional information and health claims, not… a competitor losing out because of the deception.”

Justice Sotomayor then added: “It's not that you have to use this name [Pomegranate Blueberry… Flavored Blend of 5 Juices]… you're permitted to use this name... But why are you permitted to use it in a misleading way?”

However, Sullivan [for Coca-Cola] responded: “Under the FDCA and the FDA regulations, Coke's label is, as a matter of law, not misleading.

“And once we reach that conclusion under FDCA and FDA, Lanham Act can't come in from the side and say, oh, yes, it is, because that would undermine the express preemption provision that was designed to create national uniformity.”

But Chief Justice Roberts said: “I don't know why it's impossible to have a label that fully complies with the FDA regulations and also happens to be misleading on the entirely different question of commercial competition, consumer confusion…”

The arguments in a vacuum suggest a positive outcome for POM

And this is the crux of the issue, said Peter A. Arhangelsky, a principal in the Arizona office of law firm Emord & Associates.

POM, he said, is basically arguing something well-understood in advertising law, which is that you can have an FDA-compliant label, and still mislead consumers, and the Justices seemed to agree.

"POM argued that the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) does not limit private claims that are based on the misleading impression of labeling as a whole. The Justices’ questions were consonant with that argument, which is based on well-established principles of advertising law."

He added: "The Court appears inclined to preserve Lanham Act claims unless FDA has expressly resolved an issue."

A victory for Coke, by contrast, would "lessen risk in the marketplace by contracting the universe of potential claims significantly", but would also "strip competitors of valuable rights to eliminate unfair practices", said Arhangelsky.

However, it's always risky to predict how the Supreme Court will act: “The arguments in a vacuum suggest a positive outcome for POM, but we are foolish to predict an outcome from SCOTUS arguments, particularly with other Justices historically tilting in favor of federal preemption.”

Ivan Wasserman: Justice Alito also had some tough questions for POM

Similarly, Ivan Wasserman, partner at Manatt Phelps & Phillips in Washington DC, said the fact that Justice Kennedy appeared to agree with POM that Coke’s label was misleading did not mean that Coke was facing defeat.

“They are supposed to ask tough questions, but Justice Alito also had some tough questions for POM."

Meanwhile, he added: ”This case isn’t about whether this label is misleading, it’s about whether a juice manufacturer that employs a juice name and label authorized under federal labeling legislation is subject to suits by a rival under the Lanham Act.”

Arnold Friede: Justices seemed to veer pretty much off track with most of their questions

Arnold Friede, senior food and drug law attorney with Sandler, Travis & Rosenberg, P.A in Miami, was not overly impressed with the justices' questions, however.

“Based at least on their questioning of counsel, they did not appear to focus on the key issue in this case," he added.

"If one aspect of a food label—say, the product’s name itself—complies with FDA requirements, does that mean a company can create a label that, in its totality, misleads consumers?

“Or does compliance with an FDA regulation that is admittedly limited to only the product’s name insulate the entire label from claims that it is deceptive and misleading?

“Is it conceivable that the Supreme Court would hold that the sum total of the message communicated by a food label is limited to one aspect—say, the product’s name itself—and that in determining the message as a whole you don’t consider the label in its totality because FDA looked at one piece of it?

"Hard to know from the oral arguments. So I leave it to fortune tellers, not me, to predict the actual outcome."

Click on the link below for another attorney's take on Monday's proceedings: